An Apology

2021

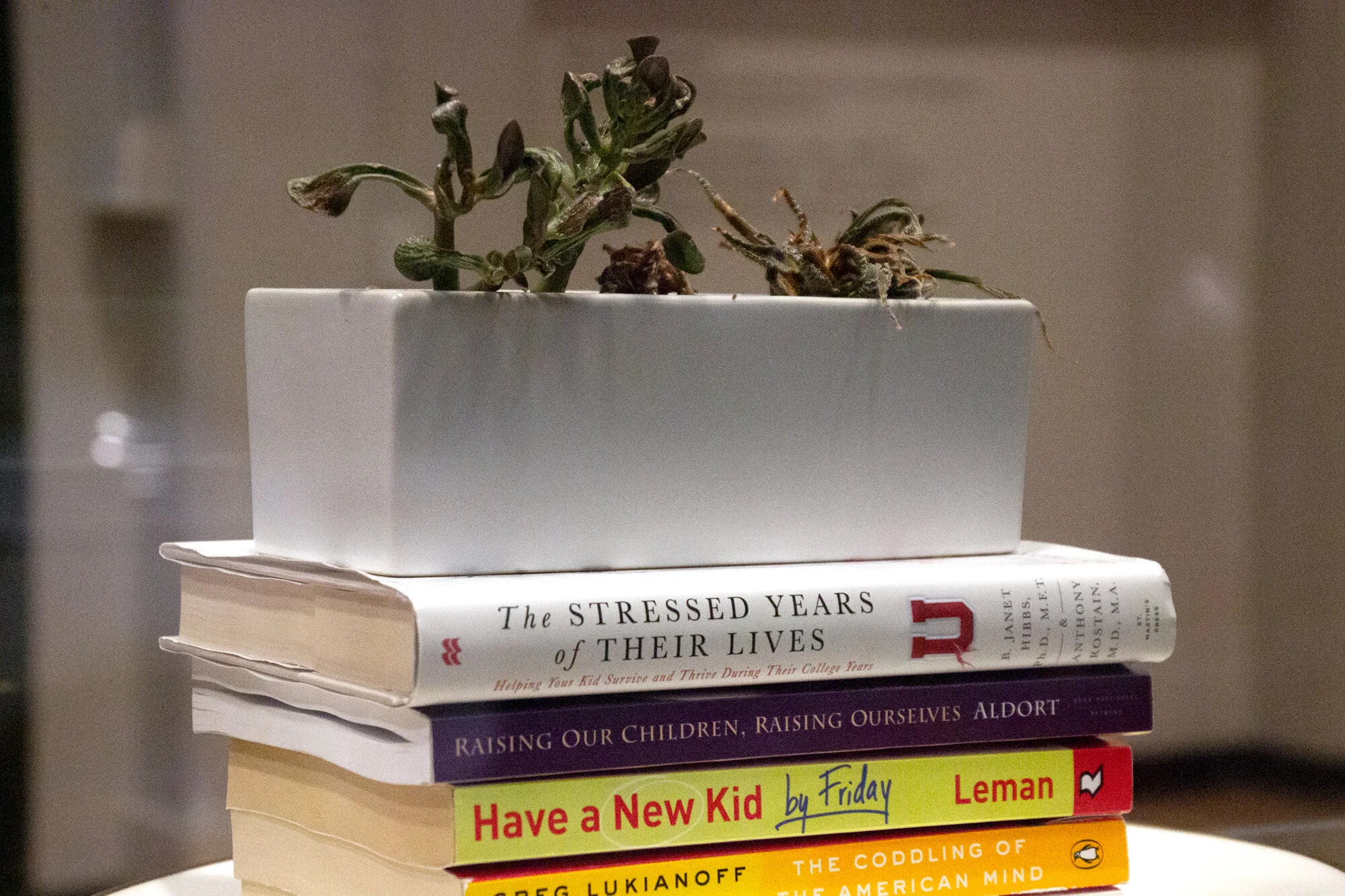

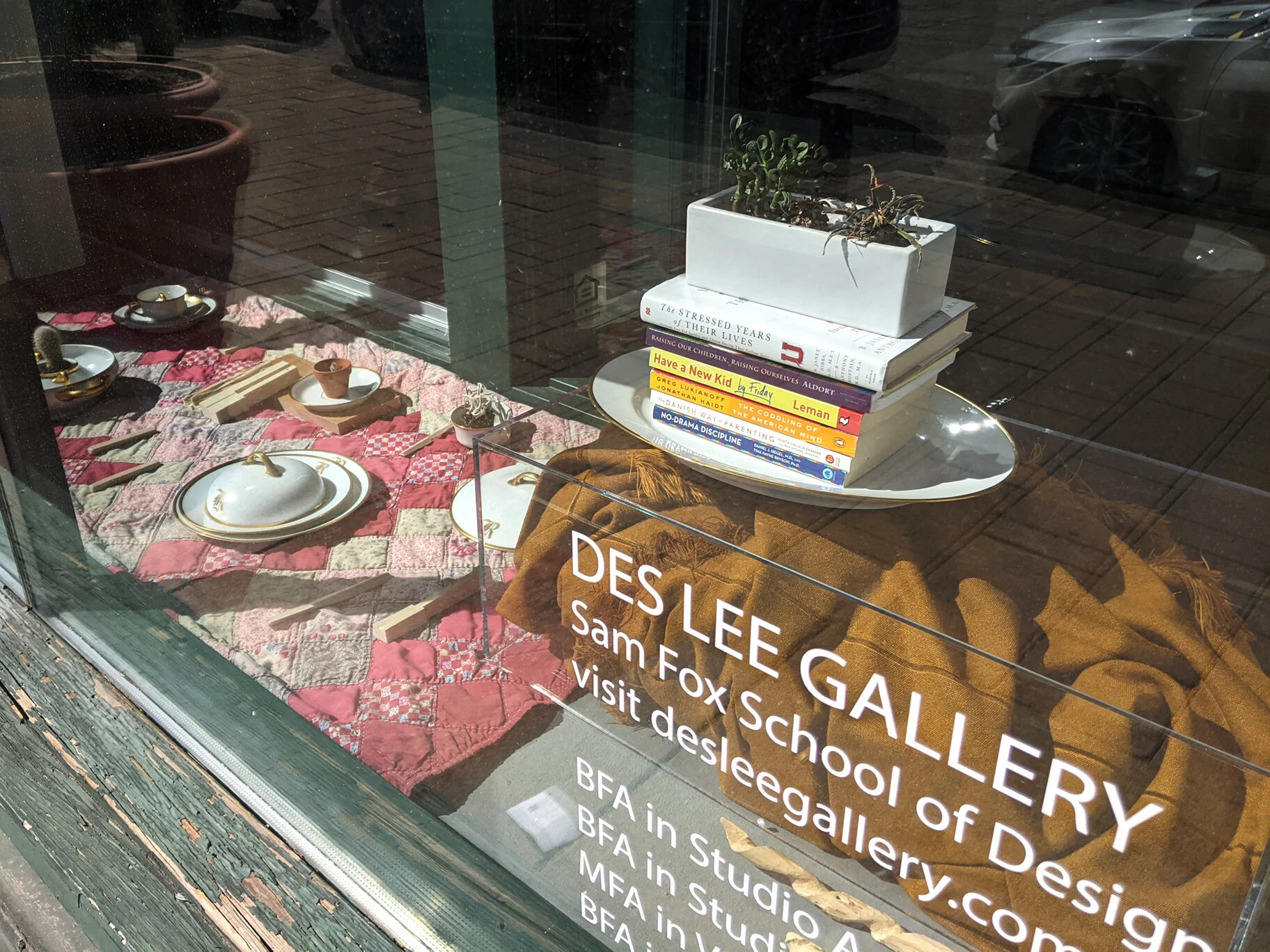

Piano leg, family china, Grandma’s quilt, Grandma’s tablecloth, wood, dying plants, parenting books.

Installed in the window of Des Lee Gallery during the Sam Fox School BFA thesis show.

The following essay was inspired by this collection of parenting books, and won second place in the Washington University Libraries' 34th annual Neureuther Student Book Collection Essay Competition. [5 minute read]

Plants, Dishes, and Stray Bullets

Parenting books do not help you garden. I know this because the first summer that I nannied full time, I bought both a series of parenting books and a set of succulents. The plants were healthy for an entire year, despite spotty sunlight and over-watering. And then something must have happened when my back was turned. All of a sudden, they were permanently shriveled and their limbs were falling off, and I did not see the change occur because it happened too quickly, or perhaps because it was too slow. The plants would whisper at me when I walked past their spot on the sill. When you adopted us, you became our mother, says one. Mommy please, please help us, pleads another. We’re dying, we’re hurt, they chorus together. You didn’t notice, didn’t notice until it was too late. I did notice, I reasoned with myself. I saw that they were suffering so I repotted them, and bought them new soil, and researched and researched what could possibly have gone wrong. They suffered still, and this convinces me that I should not own plants. I cannot protect them from whatever harms them when my back is turned, or from the changes that happen too slowly for me to see until it’s too late.

I have these same worries for the children I nanny. Because of course with both plants and children, I cannot keep my eyes on them at all times. And with children especially, I do not want to. I discover this truth as I’m nannying one day, and their mother, Sarah, is at work, and I am cleaning up from a French toast breakfast. I’m scrubbing dishes at the kitchen sink, and the window in front of me overlooks the garden. Sarah has somehow coaxed stunning vines, hearty shrubs, and flourishing herbs out of the Chicago soil. I scrape down pyrex in a kitchen that still smells like sulfur and maple syrup while Emma plays in another room with her little sister, Ellie. They did not sleep well last night, nor any night this month, and their exhaustion often turns to tantrums. Soon their voices waft down the hall and invade my watery-egg cocoon. “Come play with us!” they demand through the kitchen door. I wash the pan harder. I just want to stay here. The door swings open. I just want to wash dishes. I am so tired today, and they are so tired, and I don’t want to face all of that. Two sets of feet patter across the hardwood. I should want to play with them. That is what a good mother would want. But I turn to face their sticky blonde hair and what comes out is:

“When I’m finished with the dishes I will come and join you.”

This is a lie. I will not only finish the dishes, but also wipe down the counters and the table and organize the toys, and I know it. Resetting the space—it’s a break from tired meltdowns and make-believe. I belong to myself when I clean, when I am not consumed by the anxious protectiveness that overwhelms and terrifies me later that afternoon as I rock Ellie to sleep on the swing outside and watch Emma play with chalk. I sit on a sun-soaked cushion in the garden with a child locked in my arms, and calculate how quickly I could run and shield Emma’s body with my own if we lived in a world where a stray bullet would come flying through the fence. I think about how I would die for them. I think about how I would often rather turn my back and wash dishes than play with them. I worry that they do not sleep enough at night. I worry that I love them too much, but maybe not in the right ways.

I bought my first parenting book the day that Sarah came in from watering the tomatoes and I asked about sleep schedules. We stood by the bookshelf that held baby teeth and books about plants and books about parenting. She showed me her favorite: Raising Our Children, Raising Ourselves. Ellie clawed at her mother for attention and Sarah bent down and in her best I’m-not-mad-at-you voice said, “I am speaking with Tirzah right now. When I am done we will go finish watering the garden together, okay?” Ellie did not think that this was okay, and she climbed onto a stool and jumped on her mother’s neck.

I bought the book with expedited shipping. I thought it would help me understand why Sarah allowed Ellie to use her as a jungle gym, or why she allowed an 11pm bedtime. But I could only get through a few pages at a time before closing it carefully—always carefully, otherwise I was tempted to hurl it across the room. The author, a self-proclaimed parenting expert, says that if one child does not want to go to the zoo, mothers should cancel the entire family outing. If a child does not want to go to bed, then the whole family should adopt one bedtime—that way, no one will be awake to entertain them, and they will fall asleep. Ridiculous.

But the book had convicting whispers of truth in it. It advocated for the kind of watchful eye that I could not muster, the kind that would never favor cleaning over play time, the kind that maybe coddled, but kept a child in sight, so that nothing bad had a chance to sneak up on them. I took notes on a legal pad when I first read it, with bullet points of the least offensive messages. Scrawled towards the bottom, I wrote: “Stay present. Enjoy the activity for what it is as much as possible.” The book told me that I was going to be a terrible mother. Because I could not enjoy any activity when they were running off of 6 hours of sleep, and the syrup from a French toast breakfast was curing on the dishes. I could not stay present at all times. The book did not mention gardening, but it told me that my succulents were dying from neglect.

Reading Raising Our Children, Raising Ourselves did not stop the meltdowns, the tired crying, the slamming, the screaming, or the climbing on countertops and fridgetops and threatening to jump off of both. I’d come home to my own mother and vent. “I don’t know what to do with them. I’m not their parent. I can’t change anything.” But I soon found that this was a lie, because Raising Our Children, Raising Ourselves is not the only book on parenting. I found No-Drama Discipline after hours of scouring New York Times lists. I bought it because Sarah did not allow timeouts, and I did not know what to do when I was in the kitchen, and all of a sudden I heard a scream because Emma had hit her sister, and I was left with no discipline tactics at my disposal. I had only the guilt of Ellie’s bruise, and the knowledge that my being in the kitchen and scrubbing plates had stripped me of the title Protector. So I bought the book in a panicked and desperate attempt to protect my children from each other. And then I bought Have a New Kid by Friday after reading reviews on Amazon, and I prayed that it would protect us all from their lack of sleep. And then for Christmas that year I asked for The Danish Way of Parenting. I knew that in Denmark, when mothers go shopping, they leave their babies sleeping in strollers in the snow outside. I hoped that this book would protect us from any inexplicable stray bullets that might find their way into the backyard.

None of the books, though, taught me how to garden. None of them taught me how to care for something when you cannot keep your eyes on it at all times. I don’t know how to quell the panic that comes from your own neglect. I wonder if, someday, my own kids will wilt as I wash dishes. If, despite all my best intentions, despite all the parenting books I’ve read and will read, if they will grow too lean as they get taller. I’ll feed them well, but I’ll be busy scrubbing pans in another room when their arms and legs wither and fall off. I remind myself that children are not plants. And I buy another book.

Bibliography

Aldort, Naomi. Raising Our Children, Raising Ourselves. Bothell, WA: Book Publishers Network, 2009.

Alexander, Jessica Joelle. The Danish Way of Parenting. Penguin USA, 2016.

Leman, Kevin. Have a New Kid by Friday: How to Change Your Child's Attitude, Behavior and Character in 5 Days. Baker Publishing Group, 2013.

Siegel, Daniel J., and Tina Payne Bryson. No-Drama Discipline: the Whole-Brain Way to Calm the Chaos and Nurture Your Child's Developing Mind. New York, NY: Bantam Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2016.